Putin's Pirates of the Caribbean Tour

IBDEditorials.com

Geopolitics: Vladimir Putin blew through Latin America last week, handing out goodies to anti-U.S. regimes. But he insists he doesn't want to reopen an old spy base in Cuba, which we find disingenuous.

The scope of the Russian president's visit took the U.S. by surprise. Instead of just attending the World Cup final and a summit of BRICS countries, Putin made an unexpected visit to Nicaragua, with talk of a military land base there. He then flew to Argentina, reportedly with promises for two nuclear plants, and on to Venezuela to offer a credit lifeline.

Last but not least, Putin stopped in Cuba to sign deals on everything from electricity output to exploration for oil with Rosneft (the company whose unsavory oligarch, Igor Sechin, was the target of Wednesday's sanctions over Ukraine). There was also a dramatic announcement that Russia would forgive 90% of Cuba's $35 billion debt.

But on Thursday, Putin denied that Russia planned to rebuild a spy outpost in Lourdes, a Havana suburb that was a major Soviet listening post on the U.S. in the Cold War.

For the region's most anti-U.S. regimes, Putin's trip was a visit from the candyman. But all those handouts don't come from the goodness of his heart.

Fact is, Russia knows very well what the stakes are in the greater Caribbean, or the U.S.' "near abroad" as the Russians call it.

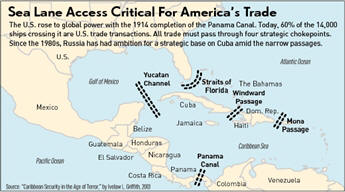

And geography is key, argues historian and geographer Robert D. Kaplan. The greater Caribbean, he argues, is the source and key to America's global rise, beginning with the 1823 Monroe Doctrine that cut out Europe's colonizers as players in the area.

"Rather than seek to keep European navies out of the Caribbean altogether, President Monroe sought only to keep them from reestablishing footholds on land in the regime," Kaplan says in "Asia's Cauldron," describing China's similar policy in the South China Sea. "The Monroe Doctrine was far more subtle than commonly supposed."

Kaplan believes that once the U.S. focused on the greater Caribbean, it was in a position to build the Panama Canal by 1914. With new territories won from Spain after the 1898 Spanish-American War, the U.S. became a two-ocean global power.

Russia knows this, which explains its keen interest in shoring up Caribbean ties with impoverished local despots. It has been playing this game since the 1980s, as U.S. defense documents show.

The idea is to strike America at its historic source of strength, as well as its critical economic power point. No wonder Russia wanted a spy base, as reported by Kommersant, a newspaper Putin frequently fights.

The Gulf of Mexico's economic importance cannot be overestimated. Every port on its seaboard has been expanding ahead of the Panama Canal widening, a $5.2 billion project that will double trade and traffic. Already 14,000 ships pass through its locks annually, and 60% involve trade with the U.S.

What an advantage for Russia to have an outpost in the Caribbean. Putin also knows a lot about timing, and with U.S. defense cuts that included a 26% cut in the Southern Command's fiscal 2013 operating budget, it's clear he sees the U.S. as disengaged — creating the perfect opportunity to act now.

"We should remember that our friends and allies are not the only ones watching our actions closely," testified Southern Command commander Gen. John Kelly last March. America's enemies "will have the opportunity to exploit the partnership vacuum left by reduced military engagement."

Based on his recent visit, Putin heard that loud and clear.